Breeds & Feeding

Today’s pigs are bred and fed to be leaner than the pigs of yesteryear. Compared with pigs from the 1950s, today’s model has slimmed down considerably, with 75 percent less fat. Around World War II, pigs averaged 2.86 inches of backfat compared with less than 0.75 inches today. At the time, lard was in demand for use in manufacturing ammunition.

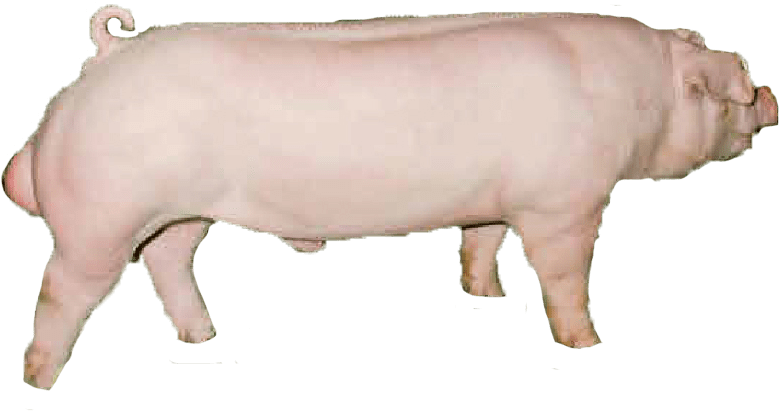

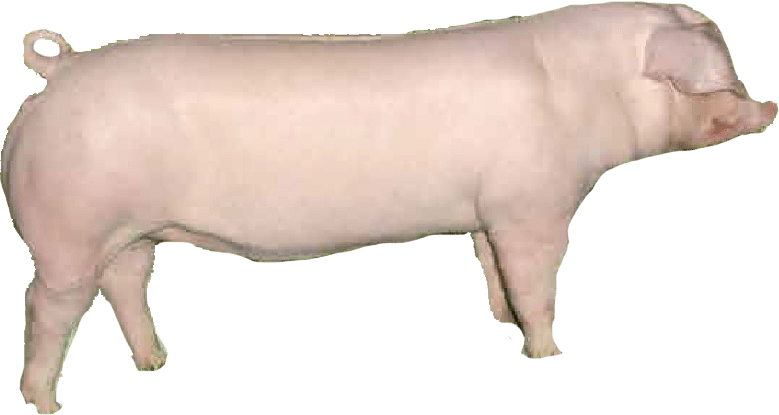

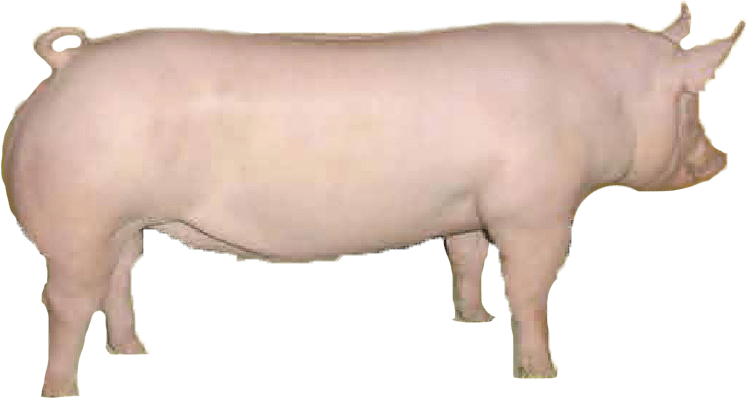

Consumers, and consequently packers, prefer lean pork, and producers are raising leaner, heavier- muscled pigs to satisfy these demands. The leaner pork is the result of new technologies in hog production and superior genetics. Producers use purebred seedstock of eight major swine breeds, which are:

- Yorkshire (or Large White)

- Duroc

- Hampshire,

- Landrace,

- Berkshire,

- Spotted,

- Chester White

- Poland China

Berkshire

Chester White

Duroc

Hampshire

Landrace

Poland China

Spotted

Yorkshire

Producers also use various genetic lines derived from these breeds. Virtually all market pigs are produced by crossing purebred breeds or using multi-genetic lines to take advantage of heterosis or hybrid vigor.

Heterosis is a biological phenomenon in which the offspring of a mating of two separate breeds or lines performs better than the average of their parents. Crossbred offspring, such as the pork industry’s SYMBOL III (described on the previous page) grow faster, have lower mortality rates and convert feed to meat more efficiently. Symbol III is a visual image of the ideal pig.

Rotational breeding systems involve the successive use of boars of different breeds and the retention of gilts that are superior for growth rate, leanness and reproductive potential (as evidenced by their mothers’ reproductive record). These systems reduce out-of-pocket breeding stock expenses since replacement females are home-raised.

However, the retention of gilts from all sires means that all sires must be selected for superior genetic potential for carcass (backfat, muscling), production (feed efficiency, growth rate) and reproduction (pigs per litter, milking ability) traits. Boars that are above average in all three types of traits are not likely to be truly superior in any one area.

Terminal breeding systems involve crossing boar lines selected strictly for carcass and production traits with gilt lines that are selected mainly for reproductive potential. These matings, usually involve artificial insemination (AI) and produce offspring that are all marketed (therefore the name “terminal”), with no gilts retained for breeding.

Since terminal boars are selected without concern for reproductive potential (remember that no gilts will be kept from the matings), ones that are truly exceptional for carcass and production traits can be used for breeding. The same is true of gilt lines. Emphasis can be placed on reproduction, with other traits being important but secondary.

Gilt lines used in modern terminal breeding systems involve mainly the white breeds – Yorkshire, Landrace and Chester White. These breeds are generally superior in reproductive traits, such as litter size, milk production and docile temperament. Most terminal sire lines use the colored breeds, which are generally more durable, leaner and heavier muscled.

Today, pork production combines many inputs into a complex process of converting feedgrains, high- protein feed ingredients, vitamins, minerals and water into live hogs and eventually, pork and pork products. This ultimate goal is attained by five basic production systems:

- Farrow-to-finish farms that involve all stages of production, from breeding through finishing to market weights of about 270 pounds.

- Farrow-to-nursery farms that involve breeding through marketing 40- to 60-pound feeder pigs to grow-finish farms.

- Farrow-to-wean farms that involve breeding through marketing 10- to 15-pound weaned pigs to nursery-grow-finish farms.

- Wean-to-finish farms that involve purchasing weaned pigs and finishing them to market weights.

- Finishing farms that buy 40- to 60-pound feeder pigs and finish them to market weight.

Feed is the major production input to the pork production process. In fact, feed accounts for more than 65 percent of all production expenses. The average whole-herd feed conversion ratio, or pounds of feed required per pound of live weight produced, for the U.S. pork industry is about 3.0 to 3.2 and is improving (getting lower) steadily. This figure includes the feed fed to boars and sows.

For comparison, consider that beef cattle take 7 to 10 pounds of feed to produce a pound of live weight, and broiler chickens require about 2 pounds of feed per pound of live weight produced. The most efficient U.S. swine herds have whole-herd feed conversion ratios under 3.0.

A variety of feed ingredients is used in proper proportions to produce “balanced” diets for pigs at each stage of their development. Corn, barley, milo (grain sorghum), oats and sometimes wheat are used to provide dietary energy in the form of carbohydrates and fat.

Oilseed meals, mainly soybean meal, are the major source of protein, the building block of muscle and other organs. Vitamins and minerals, such as calcium and phosphorous, also are included in balanced diets.

Young pigs usually are fed a diet containing 20 to 22 percent crude protein. Diets are changed when pigs reach pre-determined weights in order to balance the amounts of nutrients that the pigs consume with what they actually need. The balanced diets improve growth and performance, while reducing the amount of nutrients excreted. Crude protein levels usually drop by increments of 2 percent until pigs are consuming a 13 to 15 percent crude protein diet at finishing. Concentrations of other nutrients are changed in a similar fashion.

The US Industry

We take care of the quality and safety of US pork products sold to the world’s consumers.